That said, there is still a lot for me to enjoy in this beautiful movie, and I thought about it for days after watching it. My observations are bound to be filtered through a Western lens, and I won’t be able to pick up on all of its nuances. I can’t speak to the movie’s treatment of class, or its portrayal of sadaejuui as Park Chan-wook mentioned it in an interview (a Korean term describing a notion of people of a smaller nation worshiping the power of a bigger nation of their own volition). It’s ripe with the surprising twists and turns of a sensation novel of the Victorian era.Ī disclaimer: I have watched the movie in its German dubbing, not in its Korean and Japanese original. When it deviates, it’s still firmly grounded in the book’s spirit. Up to a point, the movie follows the beats of the book. Every shot indulges the audience with its beauty.

Everything’s offered up for the main character Sook-hee’s pleasure.

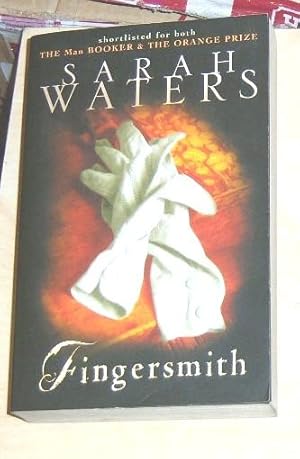

The Handmaiden offers a similar richness in textures and materials. It revels in soft leather gloves, corsetry and buttons without blotting out the sweat stains. Fingersmith indulges in the material pleasures of the Victorian era. Sarah Waters called the movie very “faithful” to her book, and it is. And yet, director Park took the twist and twisted it again so cleverly that I was as surprised as with the book. The movie kept the three-act-structure of the book, and I knew what was coming. When reading, I wasn’t prepared for the big plot twist at the end of the first part of the book. Despite this change in location and time, the movie follows the book’s plot closely - until it doesn’t. The Handmaiden transports the plot of Fingersmith from Victorian England to Korea in the 1930s under Japanese occupation.

Its beautiful, calm shots hide a thick plot of layered manipulation. The novel’s adaptation The Handmaiden (2016) achieves something similar with its lush aesthetic. The first time I read Sarah Waters’ novel Fingersmith, I was struck by its beautiful prose.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)